Asteroid mining boom or bubble?by Jeff Foust

|

| “These spacecraft really are a little bit bigger than your laptop,” Faber said of DSI’s planned Firefly and Dragonfly spacecraft. “They’re small spacecraft with amazing capability.” |

If space tourism seemed at least a little like science fiction, then the idea of asteroid mining seems a lot like it. The idea of individuals, corporate conglomerates, and governments sparring with one another as they seek to harvest the material wealth of asteroids offers writers a rich vein, so to speak, of drama that draws parallels to terrestrial mining rushes in history. Many space advocates have also long hyped the potential wealth in asteroids, from precious metals to volatiles, which could reshape the economics of spaceflight and even terrestrial industries. But the idea of lassoing even a small near Earth object (NEO) and extracting materials from it seemed like, well, science fiction, given the current state of space capabilities.

Some companies, though, are challenging that perception. Last April, Planetary Resources announced its plans to develop a series of spacecraft to prospect and, eventually, extract volatiles and other materials from NEO, perhaps within a decade (see “Planetary Resources believes asteroid mining has come of age”, The Space Review, April 30, 2012.) Last week, a second startup announced its plans to enter this market on potentially an even more aggressive timescale. However, are we seeing the beginning of a new industry sustainable over the long term, or is this, like some previous commercial space efforts, a bubble that will soon pop, taking with it some or all the companies involved?

The new asteroid mining venture, Deep Space Industries (DSI), unveiled their plans at a press conference Tuesday in Santa Monica, California. The company features a number of familiar faces for those who have followed space entrepreneurial and advocacy efforts over the years. Rick Tumlinson, co-founder of the Space Frontier Foundation and one of the key people involved with MirCorp’s ill-fated effort to commercialize the Mir space station, is DSI’s chairman of the board. The CEO is David Gump, who most recently was president of Astrobotic Technology, one of the leading competitors in the Google Lunar X PRIZE competition. John Mankins, a former NASA official who has been a leading advocate for space-based solar power, is the company’s CTO.

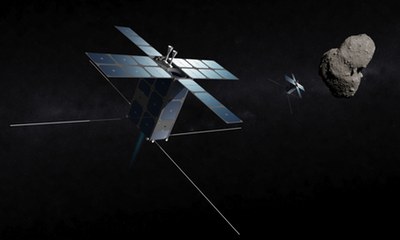

DSI’s approach is similar to Planetary Resources, making use of small satellites to prospect NEOs. An initial class of spacecraft, 25-kilogram vehicles called Fireflies, would launch starting as soon as 2015 to fly past asteroids, collecting data on the structure and composition of these bodies. Following these short-duration (two to six months) missions, DSI would fly Dragonfly spacecraft to targeted asteroids. These slightly larger spacecraft, weighing a little over 30 kilograms, would rendezvous with asteroids and collect samples for return to Earth on round-trip missions lasting two to four years. Later Harvester missions would bring back a few hundred tons of asteroid material for commercial utilization.

The Firefly and Dragonfly spacecraft will make use of CubeSat technology, a ten-centimeter-cubed form factor that has become increasing popular as building blocks for economical small satellites (see “CubeSats get big”, The Space Review, September 10, 2012.) Illustrations of the Firefly spacecraft released by DSI make it look like a “6U” CubeSat, with six CubeSats linked together into a single spacecraft, while Dragonfly looks like a 12U CubeSat. However, Daniel Faber, CEO of the Heliocentric group of companies and part of the DSI team, cautioned that illustrations contain some “artistic license” and are only representative of the actual design.

“These spacecraft really are a little bit bigger than your laptop,” Faber said. “They’re small spacecraft with amazing capability.” The company, he said, would launch several spacecraft at once to guarantee mission success even if some spacecraft fail. Tumlinson later said a three-spacecraft Firefly mission to a NEO would be priced at $20 million.

| “We see it as complementary competition,” Tumlinson said of Planetary Resources. “One company may be a fluke. Two companies showing up? That’s the beginning of an industry.” |

Also like Planetary Resources, DSI sees propellant from volatiles contained in NEOs as a likely initial market. “The biggest, earliest market for propellant in space is communications satellites,” Gump said, noting that the lifetimes of such spacecraft in geosynchronous orbit are often limited by their supply of stationkeeping propellant. “We can extend the lives of these satellites with asteroid-derived fuel at an economical price.” He added that DSI has been in discussions with an unnamed communications satellite company, who is “intrigued” by this concept. (One challenge not mentioned at the press conference is that many such satellites either use hydrazine propellant or electric thrusters that use xenon, neither of which is readily found on asteroids.)

From this initial market, Gump said DSI would move on to building structures in orbit using asteroid material, starting with communications platforms that would be too big to launch from the ground and, later, ever larger solar power satellites. The company spent part of the 90-minute press conference talking about a 3D printer technology designed to work in weightlessness that could turn asteroid raw materials into printed parts that could be used for these applications. Eventually, Gump said, DSI will return platinum group metals to Earth for sale.

Those revenue sources, though, won’t be available until the early 2020s at the earliest. In the meantime, Gump said the company plans to sell data collected by its missions, including samples returned by Dragonfly missions, to government agencies and private collectors. The company is also interested in selling corporate sponsorships for its missions.

In addition, DSI expects to get technology development contracts from NASA to test out some key technologies on the company’s missions. Gump said company officials recently briefed officials at NASA, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and “we found a great hunger that we could get space missions done at a much lower cost using CubeSat technology and a private sector approach.”

But is there really room for two companies in a market—asteroid mining—when a year ago there were none? “We see it as complementary competition,” Tumlinson said. “One company may be a fluke. Two companies showing up? That’s the beginning of an industry.”

For that assertion to be true, though, the two companies have to be equals, or at least similar to one another. And while there are a number of similarities between Planetary Resources and DSI, there are many differences as well.

| Either or both companies could fail quickly, but success is a long-term proposition. |

Planetary Resources, at the very least, has a head start, having announced its plans nine months earlier, and also seems on firmer ground. A key point it emphasized when it went public was the A-list investors it has, from Google’s Larry Page and Eric Schmidt to Ross Perot, Jr. The company has facilities in the Seattle area where it is working today on prototypes of its Arkyd-100 series of space telescopes. Just last week, the company posted an update where Chris Lewicki, Planetary Resouces’s president and “chief asteroid miner,” showed off the company’s facilities and an Arkyd-100 model spacecraft, weighing just 11 kilograms.

DSI, by comparison, is still establishing itself, having been around only six months. The company’s headquarters are in the Washington, DC, suburb of McLean, Virginia, but it has not determined where it will build the Firefly and Dragonfly spacecraft; Tumlinson said the company is looking at locations in the Los Angeles and Houston areas. Gump said the company has “some investors” onboard, “and one reason for holding this press conference is to become findable by additional investors.”

Both companies, though, will have to wait for years to fulfill their long-term goals of accessing asteroid resources and selling them to various customers. The companies will have to sustain themselves with their investment and ancillary lines of business, looking more like smallsat manufacturers and technology development companies than asteroid miners. Either or both companies could fail quickly, but success is a long-term proposition. Turning asteroid mining from science fiction to reality is something that will take years to develop. The bubble could pop quickly, but the boom will take place in slow motion.